“Yes!” I thought,

reading Peter Gray’s blog post about the importance of stories for young

children. My mind traveled back to all of the stories I have read, and acted

out with, young children over the course of my career. Dr. Gray focused

specifically on reading to children; how this act has been singled out, with

good reason, to be more important to the future education of children than most

others. His excellent point is that there is more to story reading than cuddles

and close relationships, though these are essential for human growth and development,

not to mention human joy!

“Knowing how to deal with evil as well as love, how to

recognize others’ desires and needs, how to behave towards others so as to

retain their friendship, and how to earn the respect of the larger society

are among the most important skills we all must develop for a life.” These

skills are actually something we learn all through life, but giving children

stories to reflect on gives them a huge advantage, psychologically, as an early

start on braving human relationships, and fostering skillful interactions. Dare

I say, also, that stories help children learn to be wise rather than right, as

in, “right, not wrong”?

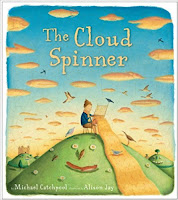

One book that, surprisingly, became a favorite with a group

of pre-k students, and demonstrated the difference between wisdom and “might

makes right”, was The Cloud Spinner, by Michael Catchpool and Alison Jay. This

entrancing story starts out, “There was once a boy who could weave cloth from

the clouds”. The boy sings as he works: “Enough is enough and not one stitch more”.

Immediately, Alison Jay’s illustrations captivated our children. The hills and

houses reflect the moods of the characters. Our children noticed this before I

did! Smiles on hills are made of trees, and sheep. Houses smile with windows

and doors. In the beginning, nature is in harmony because the boy with his

magical loom only makes what he needs. One day, the king notices the boy in a

crowd and madly desires clothing, of both himself and his family, made of the

clouds. He commands the boy to weave for him. The boy balks at first: “It would

not be wise to have (so much fabric) made from this cloth. Your majesty does

not need it.” The king is apoplectic, commanding the boy do his bidding. So he

does. He weaves, and the illustrations reflect the sadness of the task with darkening

color and forlorn hills.

The Cloud Spinner does not so much have a cheerful ending as

a wise and uplifting one. The children, absorbed in it, noticing details of the

varying shades of color that reflect the boy’s, and the King’s daughter’s moods

(She helps him to reverse the tragic disappearance of clouds that cause

drought, and discontent among the people). The King and his family are

astounded by the gratitude of the people after the clothing he ordered is

turned back into clouds, causing welcome rain. The boy and princess exult in

the restoration of a wise order in nature and among humans. The children,

sitting before me, sigh in contentment.

Our preschoolers learned about what greed was, some

demonstrating it by acting out the concept—“Mine! Mine!”, with gestures of

raking in loot! A teacher took up the phrase, “Enough is enough and not one

____ more” when children wanted ALL the blocks, or pizza. And, amazingly, this

story was one of the most requested during reading time, rivaling Dragons Love Tacos!

If children have a deep interest in this or any other story,

it is wise to follow their direction and see what they do with it. Our children

drew and painted clouds in an array of colors, and told stories with greedy

characters and children with magical powers. If you teach to standards, these activities

can be used to fulfill them—Language arts, social studies, even math and

science. Arts standards go without saying, and the text of the song can be set

to music. Ask any child! They will have a tune before you know it!

Children do need stories to make sense of feelings and wise

social interaction. They need myth, I dare say, to hold on to the important

values of society. As human interaction and social relationships are varied,

so, too, are the stories we read and tell.